Meditation Basics

“Zen is immediate experience of our prior Buddha Nature, already present in the human form, always awake, here now.”

-Dechen Wangdu

Posture

To practice seated Chan meditation, one must be able to sit in a balanced position that allows the free and natural flow of breath. If the body is balanced the mind will be balanced as well, since the two are really not separate. One may do seated Chan meditation on a round meditation cushion, on a meditation bench, or on a regular chair.

A round cushion may be used in one of two ways: sitting on the flat part of the cushion or straddling the cushion, which is in an upright position like a wheel. The straddle method is very similar to sitting on a meditation bench.

For most people who want to attempt a cross-legged sitting position on a flat cushion, the “Burmese” posture is very reasonable. The dominant leg is crossed to the inside, while the other leg is crossed to the outside. Both legs are on the floor or the square mat, with the knees touching down. The ankles are never crossed, nor does one leg rest on the other. A small support cushion may be used if one has difficulty getting the knee to touch down.

In the “Quarter Lotus” position, the top of the outside foot is placed on the calf of the inside leg. Be very careful, as this position may cause the inside leg to fall asleep due to pressure on the calf. In the “Half Lotus” position, the top of the outside foot may be placed atop the inner thigh with the sole of the foot pointing upward. In the “Full Lotus” position, the tops of both feet are placed, soles up, on the opposite thighs. This position is considered to be the most stable position for seated meditation.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Never, under any circumstances, attempt to sit in a Half Lotus or Full Lotus position unless you have first done a series of stretching exercises taught to you by a qualified instructor such as a Yoga teacher or Personal Trainer! You risk doing serious damage to muscles, ligaments and tendons if you attempt a Full Lotus posture without being stretched out properly. Remember, a gradual, consistent program of stretching exercises may enable you to attain a Half Lotus or Full Lotus position in time. NEVER, EVER try to force your way into a cross-legged sitting position!

Stretching is extremely important when attempting to attain a comfortable, stable sitting position of any kind. You should always do some kind of gentle stretching both before and after you meditate in any seated posture. Exercises such as Tai Chi, Qigong or Yoga are very helpful in this regard.

Using a Chair, Sitting on a Bench, Straddling a Cushion

Using a meditation bench or straddling a round cushion requires one to straighten the upper body in the same way one does when sitting on the flat part of a cushion. The rules of posture, hand position and breathing are the same as indicated below.

Adjusting Posture

A balanced posture insures that one’s breathing is slow and even and that one’s natural bodily energy flows easily. The head should be held erect, but not stiffly, atop the body. Don’t try to sit up as straight and tall as you can, as this can lead to back pain. To straighten the back, simply move the navel forward a few inches, supporting the vertebrae from beneath. Place the tip of the tongue behind the top of your front teeth at the gum line. Tuck the chin in slightly. The gaze gently rests on a point no more than three feet in front of you on the floor. The eyelids hang about halfway down the eyeballs. Don’t squint, but don’t close the eyes entirely either. Relax the shoulders! This allows you to breathe naturally.

The Hands

One way for beginners to balance the hands is to place them, palms up, on each thigh. Place the flat part of the thumbs over the tips of the index fingernails. Allow the other three fingers to come together in a gentle curve with no space between them.

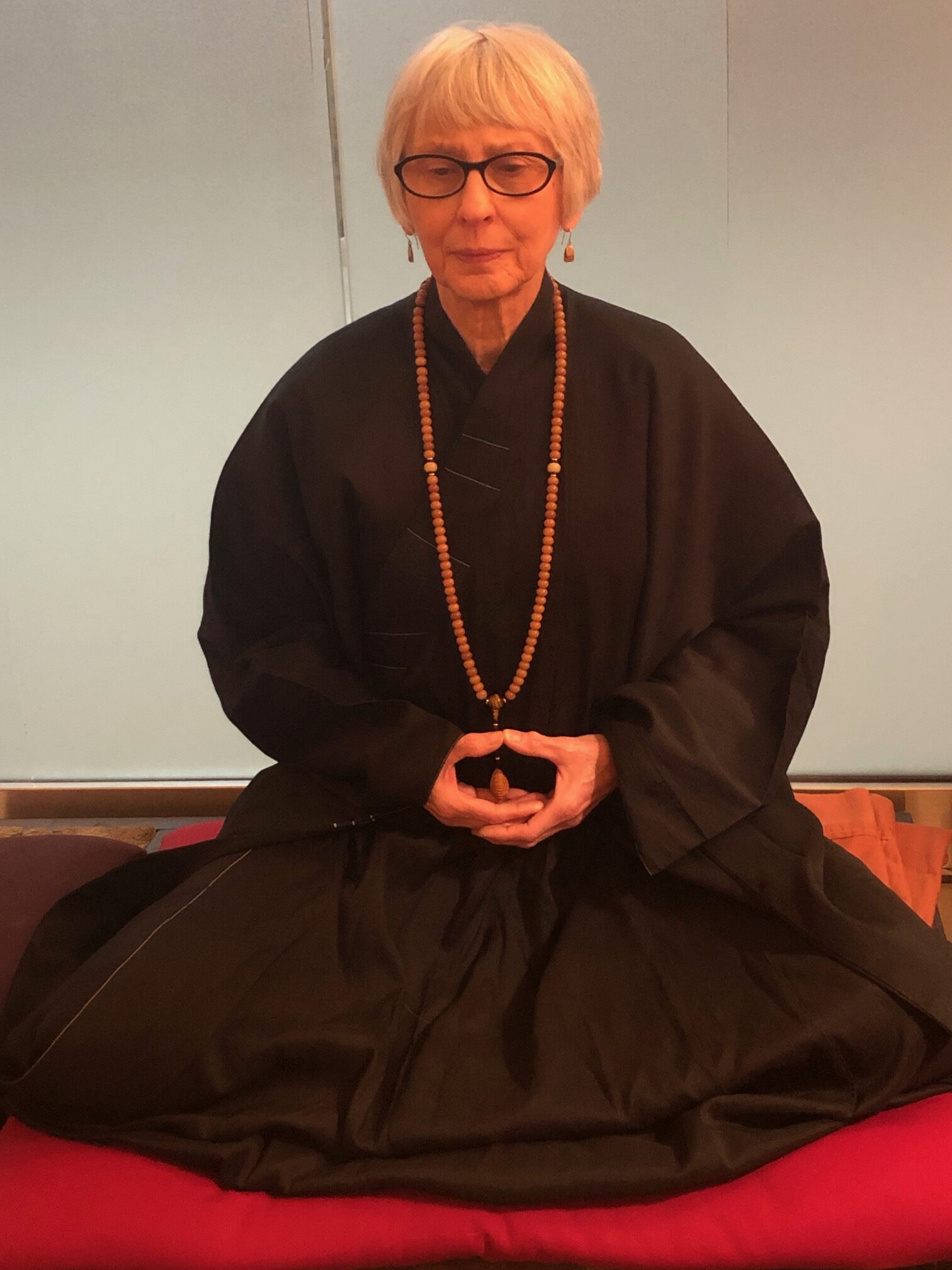

A more traditional hand position involves what is known as “quieting the dominant hand.” Place the inside edge of the little finger of your dominant hand against the abdomen; the palm faces upward. Place the other hand, palm up, on top of the dominant hand. Now place the tips of the thumbs together lightly, as if you are holding a large egg in your hand. The point at which the thumb tips touch should be at the level of your navel. The thumb tips do not touch the body. Adjust the hands as needed to maintain this position

Breathing

The breaths are slow, deep, gentle, and absolutely silent. Breathe gently through the nose into the abdomen instead of the chest cavity, allowing the abdomen to gently inflate in the in-breath and deflate on the out-breath. Breathe into the abdomen, but don’t try to see how much breath you can cram into it. Then gently release the breath back through the nose.

The Basic Practice

Pay attention to your breath for a minute or two, then move your attention to your mind and simply, objectively, observe it without any comment, analysis, comparison or recollection. Continuously repeat this process of being aware of the breath, then observing the mind. Remember that mind encompasses more than just what’s going on in your head; it is consciousness itself.

Alternate Practice: "Watching the Mind"

After a moment or two of breath awareness, focus your attention on one or more of those qualities which are part of your Essential Awakened Nature. Things such as Compassion, Wisdom, Loving-Kindness, Joy, Focus, Equanimity, etc. Objectively observe one or more of these qualities without any comment, analysis, comparison or recollection. In both practices, be sure to release any thoughts, sounds or physical sensations which arise as soon as they appear, and simply return to your meditative practice. Do this any time these things arise.

Thoughts may be especially distracting since they come and go so quickly and may return again and again and again. But even if you must re-center your attention constantly, that’s all right. You are learning how to calm and harmonize the mind as well as how to recognize distractions and return to a state of mindful concentration. In Chan practice you really cannot make a “mistake,” since it’s simply a process of staying and returning, so there’s no such thing as “great” Chan practice or “bad” Chan practice. Just Chan practice.

NOTE: More intricate and energetic practices such as gongan (J. koan), huatou and silent illumination should only be practiced under the guidance of a qualified Zen teacher.

Walking Meditation

The practice of walking meditation has two purposes: it balances the quiet act of sitting with a slightly more active form, and it gives practitioners a chance to stretch their legs out. The walking pace itself is slower than normal, yet not extremely slow. The body from the waist to the top of the head is in the same position as it is in seated meditation, with the chin tucked in slightly and the eyes slightly downcast, the head resting comfortably atop the spinal column.

The focus of your concentration during walking should be the entire body. Simply observe the entire act of walking, from the point where your feet touch the floor to the top of your head, as your body moves around the hall. Remember to bring your attention back to the walking body whenever anything takes it away.

The hand position for walking practice is as follows: with the dominant hand, gently grasp the thumb of the non-dominant hand as if you were grabbing a hammer. Allow the fingers of the non-dominant hand to fall across the clasped fingers of the dominant hand. Relax your shoulders, let the arms drop straight down, and place the thumb of the dominant hand against the navel, then rest the knuckles of the dominant hand against the abdomen.