History of Meditative Pure Land Practice

The unified practice of Chan and Pure Land, known in Chinese as “Chanjing Yichih,” has a long history. As early as the 4th century C.E., Master Huiyuan (334-416), considered to the be first Pure Land Ancestor, incorporated meditative discipline into Pure Land practice.

Dayi Daoxin (580-651), the Fourth Ancestor of the Chan school, taught what he called the “Samadhi of Oneness,” utilizing the recitation of the Buddha’s name to pacify the mind. It should be noted that since this practice involved reciting the name of any Buddha (a practice dating back to the origins of Buddhism) it was not specifically designed to produce rebirth in the Realm of Bliss, but it did act as a bridge linking Chan and Nienfo practices. Daoxin taught that the Pure Mind is the Pure Buddha-Land.

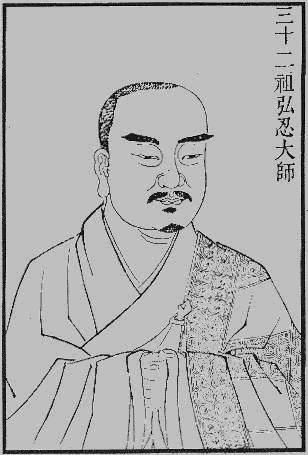

The unified practice was also advocated by the Fifth Chan Ancestor Daman Hongren (601-674) who saw recitation as a good practice for beginners. Hongren also advocated the visualization practices laid out in the Visualization Sutra.

Buddha recitation not concerned with rebirth was taught by a number of Hongren’s disciples including Fazhi (635-702), the Fourth Ancestor of the Ox-Head School of Chan. It was also put forth by the Jingzhong School which was descended from Xiangyan Zhixian, one of the Fifth Chan Ancestor’s 10 eminent disciples, in the early 8th century CE.

Descendents of Zhixian who advocated the unified practice included Wuxiang, a former Korean prince who made invocational Nienfo practice a key part of the Dharma Transmission Ceremony. Although the practice was still not centered around Buddha Amitabha or rebirth in the Realm of Bliss, it marked the first time that Nienfo practice was explicitly adopted as part of a Chan school. Subsequent schools which taught Nienfo as part of their training included the Baotang School, the Xuanshi Nienfo Chan School and the Nanshan Nienfo Chan School.

Ancestor Cimin (679-748) is said to have been the first Pure Land Ancestor to advocate harmonizing Pure Land practice and Chan. Cimin developed his Pure Land faith after a pilgrimage to India, where he was inspired by stories centered around Buddha Amitabha and Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara.

The Chan Ancestor Baizhang Huaihai (720-814), who wrote the “20 Monastic Principles” which were the blueprint for Chan monastic practice, included “Recitation of the Name of Buddha Amitabha.”Baizhang stated, “In religious practice, take Buddha Recitation as a sure method.” The practice of chanting Amitabha’s name during a Chan monk’s funeral was also put forth by Master Baizhang.

The Tang Huichan Persecution (845 C.E.) and the Hueichang and Shizong Persecutions of the late Chou Dynasty (10th century CE) served to bring Chan and Pure Land even closer together. These government crackdowns on Buddhist sects enervated the academically oriented Buddhist schools such as the Tientai and Huayan sects. Correspondingly, the rise of Neo-Confucianism drew many speculative thinkers away from those schools. But the Chan and Pure Land schools, marked by their emphasis on practice, their extreme degree of portability and their non-reliance on Imperial patronage, survived intact. By this time, the Chan school had incorporated true Nienfo Amitabha practices into its training regimens, and the Pure Land school had incorporated more meditational elements into its own system.

The Ch’an monk and Pure Land practitioner Yungming Yenshou (905-975) is said to have been the key figure in the synthesis of Ch’an and Pure Land during this period. He taught that the Pure Land is the Realm of the Purified Mind.

The unified practices were taught in Vietnam by the Thao-Duong School, founded by the Chinese monk Caodang, who was taken to Vietnam as a prisoner of war in 1069 C.E. Other eminent Chinese monks who promoted unified practice were Zhuhong (1535-1615) and Hanshan (1546-1623).

During the 17th century CE, the monk Yinyuan Lungji, known as Obaku in Japanese, brought the unified Chan/Pure Land practice to Japan. His school is known as the Obaku Zen School, and survives to this day as a minor sect in the shadow of the much more influential Soto and Rinzai Zen sects.

The unified practice of Chan and Pure Land continues to this day, although it was de-emphasized in the major Japanese Zen schools. The large Shin sect of Japanese Pure Land Buddhism discounts any efforts on one’s own part to attain Enlightenment; superficially, Japanese “Other-Power” Pure Land Buddhism and “Self-Power” Zen Buddhism do not complement each other the way the Chinese Chan and Pure Land schools do. However, there are recent movements which may yet be influential in returning Japanese Zen to its syncretic roots.

In the 1970s, the formation of the Zen Shin Sangha by Reverend Koshin Ogui in Cleveland, Ohio was one of the first instances of a Shin Buddhist priest in the United States combining Japanese Zen and Pure Land practices. Similar movements have been reported in England, continental Europe and India.

As the esteemed Chan Master Xuyun (1840-1959) put it, “All the Buddhas in every universe, past, present and future, preach the same Dharma. There is no difference between the methods advocated by Shakyamuni and Amitabha.”